THE ORCHARD ON FIRE

- 20 Apr - 26 Apr, 2024

"Your request has been denied," said the automated voice on the other end.

"What the hell," I screamed into the receiver. "I broke my leg! What is there an interaction with my pain meds, to hell with my pain meds."

The automated system didn't answer.

"Operator," I said. "I want to talk to a human. Uh, does swearing work on this one? You heartless machine…"

It didn't give me a human. I couldn't really see that being a competitive job posting, manning the complaint line for the school pharmacy.

I dialed again.

"You have reached the U of M pharmacy line! Press one to talk about a change to your prescription. Press two to request dosages for excused absences, administrative error, or other extenuating circumstance. Press three to transfer your prescription to another university…"

I pressed one. Two hadn't worked or even gotten me a person.

"Press one if your prescription may be interacting with another medication. Press two if you feel your dosage should be adjusted. Press three if you need a supplementary prescription for a project. Press four if…"

I tried pressing one.

"Please hold."

Twenty minutes of scratchy elevator music later, there was a real person, hallelujah. "Hello?"

"Hi, this is – my student number 5440981."

"Okay, I'm looking you up – what can I do for you, Skylan?"

"I broke my leg, so I've missed a class and I'm not going to make it to the later ones, but the auto–system wouldn't assign me a delivery?"

"Oh, if you have an injury like that you're supposed to call disability services to get you to class," said the person.

"What? Are you kidding me?" I demanded. "I'm already shaking, and this isn't – this isn't in the pharmacy info packet – I need the delivery…"

"Skylan, I'm seeing two previous deliveries for absences this semester – one because you were... hung over? And one because your... dog died?"

"…so?" My grandmother's dog counted, right? I loved that little fuzz ball.

"So, two is the number of dubious excuses you get per semester."

"But I broke my leg!"

"And disability services can get you to class, and if you haven't tried that, then the excuse is dubious," said the person. "No delivery, but you can still get two thirds of your dose for the day if you make it to Latin and Research Methods, and I'm sure the disability office will be happy to help you out."

"But…"

"This is the interactions line; are you on anything for your leg?"

I read the name off the bottle. She told me there were no interactions. She hung up.

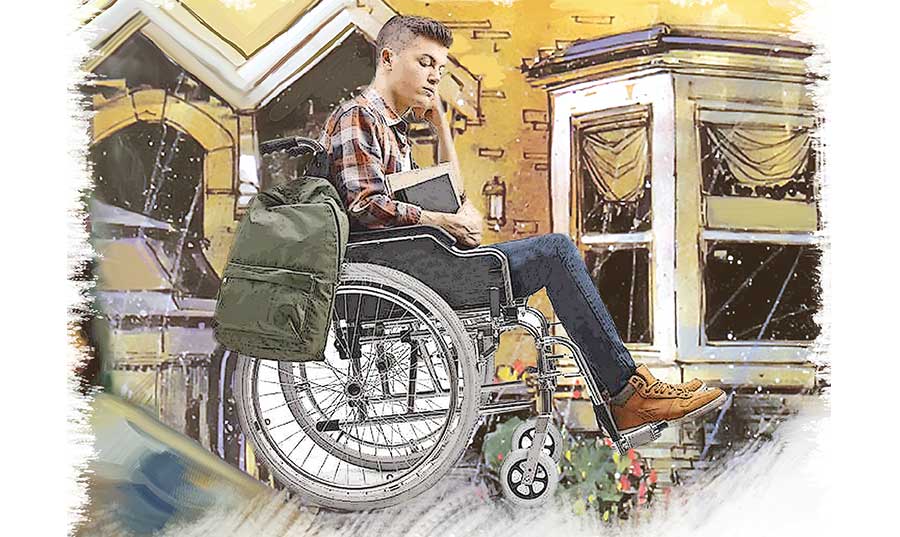

I called disability services. They showed up with a wheelchair that, at the cost of all the muscles in my arms, I rolled up the hill in time to get me to the last half of Latin. The TA wouldn't hand over a dosage packet for anybody more than five minutes late.

I got to Research Methods on time and barely made my participation quota. I got my one–third dose, time–released as though I'd already had two, painfully slow to stop the tremors. It wasn't enough; I couldn't get to sleep that night. At one in the morning I called a friend.

"Skylan? Why the hell are you calling me this early?" she mumbled into the phone.

"Your pills are little green triangles too, right?"

"Oh, you're fixing. You know they can put anything in a little green triangle, right?"

"Yeah but they might not, what if…"

"I don't have any extra, Skylan."

"Are you sure?"

"Go to hell, Skylan." She hung up.

I called three more people. One of them did have extra but his withdrawal symptoms were tiredness and headaches, not shaking, and the last thing I needed was to be addicted to somebody else's schedule on top of mine.

The next morning, the elevator was broken. I threw the wheelchair out a window and dropped out online and skidded down the stairs one at a time and got on the bus to be home.

"That was so rash, Skylan," said my mother.

"Yes, Mom, I know," I said. I was sitting on my hands so they wouldn't jitter, but it was starting to wear off.

"You'll have a lot of trouble getting in somewhere else, now."

"I know, Mom."

"You really shouldn't have been doing parkour in the first place."

"Uh–huh." If I broke into the school pharmacy, they might have packets with my name on them already sorted and stamped for the TA’s.

"Are you listening to me, Skylan?"

"No, Mom."

"You have no idea how much I wish you were still on your little treats."

"If you give me a treat I'll throw it in the toilet, Mom."

"They got me through your childhood!"

"I bet they did, Mom."

"They might let you reverse your dropping out if you asked very nicely."

"Don't think so, Mom," I said through gritted teeth. I did not want to do this twice.

I ate frozen meals and a lot of burgers from All Organic Drug Free Andy's Burgers in case there were "treats" in the homemade macaroni and I lowered my standards for a job to nothing. My mother had not yet resorted to threatening me with homelessness to get me addicted to treats again by the time I had an interview.

Mission Pharmaceuticals needed a person who was less hack–able than an algorithm to decide whose doses were printed into what shape of pills. Ever since the big Varaco hack had leaked information on a million parolees' condition–of–release drugs, so they could get the same chemicals on the street by name or formula, it was standard practice to mix it up: a pharmacist would know what you were really taking, but it might be a little green triangle or a long white lozenge or a purple circle with milled edges. Nobody could hack into an employee who decided on a whim to give a new client daisy–yellow pentagons or blue gelcaps.

This mind–numbing un–automatable task did not require a college degree.

"Remember," my new boss clarified, "people can be hacked, just not by software – but if someone asks you for information you're not supposed to disclose, it's probably going to be a secret shopper, as it were. You'll be instantly fired if you talk to one of those and may be liable for criminal charges. They might show you a suitcase full of cash, they might pretend they can prove they don't work for us or somebody who's testing you on our behalf – don't believe them."

"Got it," I said.

"Excellent," he said. "Here's the handbook of the shapes, colours, and variants we offer, Ista will show you around, and you can get started tomorrow morning."

I spent eight hours a day sitting in a cube, sometimes typing "yellow yellow yellow white blue ecru RAZZAMATAZZ kiwi–green white gold maroon" into a spreadsheet, sometimes tooling around on the internet. My trial period ended when I completely failed to notice the ostensible secret shopper cozying up to me at an office Christmas party; this constituted passing with flying colours.

"Where do I go for my work doses?" I asked my boss, when the trial was over.

"Oh, of course," he said. "Next to the payroll office."

"What's your policy on absences?"

"We give you a week of stepping down," he says. "To keep at home, according to the at–will employment agreement, see, you can wean yourself off if you quit suddenly. You can dip into it if you take a sick day or vacation day and replace it whenever's convenient for you."

I took my seven installments of step–down meds in their numbered–compartments box, threw it into the back of the utensil drawer in my delightfully Mom less studio apartment, and showed up every day in the office left of Payroll to get a lavender sphere to swallow.

When I'd been working for seven months I got a secret shopper in the form of a young–looking guy, maybe sixteen or at least picked to look that way, who "spotted my company T–shirt" in the All Organic Drug Free Andy's Burgers. "You work for Mission," he said.

"…yeah," I said.

"I have to know what I'm on," he said. "My dad puts it in everything, doses me first thing in the morning and last thing before I go to bed, I can't be away from home overnight without."

"I can't tell you anything," I said.

"You don't understand. He's, he's – I need to get out, my brother has a place but if…"

"I can't tell you anything,"

I repeated.

"For god’s sake!" he said, beginning to risk making a scene in the burger joint. "Heartless bastards, why don't you screen people you give your shit out to…"

"Can't – tell you anything," I said, visions of "treats" dancing in my mind.

"Just tell me if going cold turkey's going to actually kill me," he pleaded. "My brother can lock me up or something…"

"I can't even look that up from here," I said.

"Do you remember anything?"

"Man, I do hundreds of these things a day, you could show me a pill and I wouldn't know whether it went to a dad or a school or a cult – what are your withdrawal symptoms?"

"You think I test that? If I don't get away clean on the first try my dad's probably going to straight up kill me, I have no idea – school gives me the same thing, brown shield shapes, he got them to match it, I get one every hour…"

"Then, I don't even have a guess."

"I'm the one who's taking them! I ought to know what they are!"

"If you are over eighteen and terminate your formal relationship you have…"

"Sixteen."

"…the right to an own–expense, pharmacy–assisted offramp from – well if you're sixteen I really can't help you, I'd lose my job, dude."

"Please."

"I told you I can't even look it up from here."

His dad, presumably, honked a car horn outside, and the kid jumped and took his sack of burgers out the door, slouching.

I couldn't look it up without my work computer. But I looked it up the next day, brown shields. I didn't make many things shield–shaped; "Skylan happens not to like shield shapes" was a valid input to my vitally important un–automatable job. There were four patients on brown shields in the system. The kid had looked maybe Hispanic, so he was probably Juarez and not the Polish name or the two Korean ones.

All the drugs had code names that I had access to – RAZZAMATAZZ™ was incompatible with "wakey–wakey" and you couldn't put "night song" in a gel cap, that sort of thing, so I needed to know. Juarez was on "chipper". I didn't know what chipper was, but whoever assigned the code names was before my arrival; they might have been from pre–Varaco–hack and used ones that the Internet knew about.

I got home and looked up "chipper".

According to streetyourdrug.com, chipper was impossible to dose like Juarez had described – if you took meaningful amounts every hour of the day you'd have operations in your sleep. The pharmacist would have told Dad Juarez not to do it that way, and if Dad Juarez had ignored the instructions he'd have an epileptic kid. So Juarez Junior wasn't a very well–informed secret shopper. Wasn't actually Juarez at all; the real Juarez was on chipper, on some sane schedule, the secret shopper was making up "brown shields". That settled that.

The kid's face turned up dead on the news a month later, beaten to a pulp by his dad and passing away in the hospital. His brother, Joe Juarez, was making a big fuss about it on the news.

Mission wasn't implicated, obviously, everybody dosed their kids, it was possible to dose abusively just like it was possible to apply curfew abusively – not dosing your kids was practically neglect.

to be continued...

COMMENTS