An Epidemic

- 13 Apr - 19 Apr, 2024

He was her one possession; all else might be taken away from her, but the feeling inhabiting her heart must live, like the heart itself. By the time September had yellowed all the fields, there came a week when Phoebe's aunt, down at the Hollow, was known to be very ill; so Phoebe no longer came to care for the parson through the Sunday-school hour. But the doctor appeared, instead. "I'm Phoebe," he said, laughing, when Dorcas met him at the door. "She can't come; so I told her I'd take her place." These were the little familiar deeds which gilded his name among the people.

Dorcas had been growing used to them. But on the' next Sunday morning, when she was hurrying about her kitchen, making early preparations for the cold mid-day meal, a daring thought assailed her. Phoebe might come to-day, and if the doctor also dropped in, she would ask them both to dinner. There was no reason for inviting him alone; besides, it was happier to sit by, leaving him to someone else. Then the two would talk, and she, with no responsibility, could listen and look, and hug her secret joy. "I ain't a-goin' to meetin' to-day!" came Nance Pete's voice from the door. She stood there, smoking prosperously, and took out her pipe, with a jaunty motion, at the words. "I stopped at Kelup Rivers', on the way over, an' they gi'n me a good breakfast, an' last week, that young doctor gi'n me a whole paper o' fine-cut. I ain't a-goin' to meetin'! I'm goin' to se' down under the old elm, an' have a real good smoke."

She thinks he may drop in to see you to-night. I guess he give her to understand so." The minister chuckled. "Isn’t he a smart one?" he rejoined. "Smart as a trap! Dorcas, I 'am not finished my sermon. I guess I shall have to preach an old one. You lay me out the one on the salt losing' its savour, an' I'll look it over." "Yes, father." The same demand and the same answer varied but slightly, had been exchanged between them every Saturday night for years. Dorcas replied now without thinking. Her mind had spread its wings and flown out into the sweet stillness of the garden and the world beyond; it even hastened on into the unknown ways of guesswork, seeking for one who should be coming. She strained her ears to hear the beating of hoofs and the rattle of wheels across the little, bridge.

"O Nancy!" Dorcas had no dreams so happy that such an avalanche could not sweep them aside. "Now, do! Why, you don't want me to think you go to church just because I save you some breakfast!" Nance turned away, and put up her chin to watch a wreath of smoke. "I dunno why I don't," said she. "The world's nothin' but buy an' sell. You know it, an' I know it!' 'Tain't no use coverin' on't up. You heerd the news? That old fool of a Sim Barker's dead. The doctor, sut up all night with him, an' I guess now he's layin' on him out. I wouldn't ha' done it! I'd ha' wropped him up in his old coat, an' glad to git rid on him! Well, he won't cheat ye out o' any more five-cent pieces, to squander in terbacker. You might save 'em up for me, now he's done for!" Nance went stalking away to the gate, flaunting a visible air of fine, free enjoyment, the product of tobacco and a bright morning. Dorcas watched her, annoyed, and yet quite helpless; she was outwitted, and she knew it.

Perhaps she sorrowed less deeply over the loss to her pensioner's immortal soul, thus taking holiday from spiritual discipline, than the serious problem involved in subtracting one from the congregation. Would a Sunday-school picnic constitute a bribe worth mentioning? Perhaps not, so far as Nance was concerned; but her own class might like it, and on that young blood she depended, to vivify the church. A bit of pink came flashing along the country road. It was Phoebe, walking very fast. "Dear heart!" said Dorcas, aloud to herself, as the girl came hurriedly up the path.

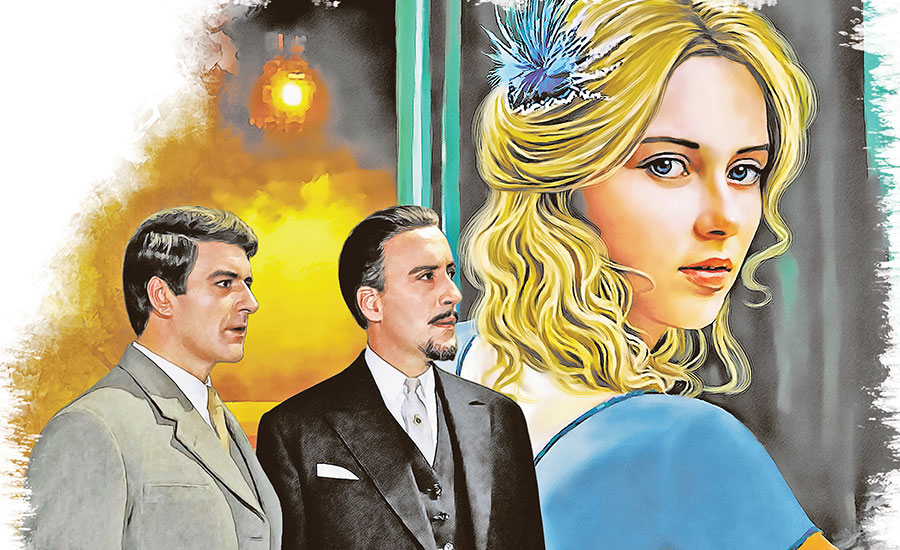

She was no longer a pretty girl, a nice girl, as the commendation went. Her face had gained an exalted lift; she was beautiful. She took Miss Dorcas by the arms, and laughed the laugh that knows itself in the right, and so will not be shy. "Miss Dorcas," she said, "I've got to tell you right out, or I can't do it at all. What should you say if I told you I was married?--to the doctor?" Dorcas looked at her as if she did not hear. "It's begun to get round," went on Phoebe, "and I wanted to give you the word myself. You see, auntie was sick, and when he was there so much, she grew to depend on him, and one day, when we'd been engaged a week, she said, why shouldn't we be married, and he come right to the house to live? He's only boarding, you know. And nothing to do but it must be done right off, and so I--I said 'yes! And we were married, Thursday.

Auntie's better, and O Miss Dorcas! I think we're going to have a real good time together." She threw her arms about Dorcas, and put down her shining brown head upon them. Dorcas tried to answer. When she did speak, her voice sounded thin and faint, and she wondered confusedly if Phoebe could hear. "I didn't know--" she said. "I didn't know," "Why, no, of course not!" returned Phoebe, brightly. "Nobody did. You'd have been the first, but I didn't want the engagement talked about till auntie was better. Oh, I believe that's his horse's step! I'll run out, and ride home with him. You come, too, Miss Dorcas, and just say a word!" Dorcas loosened the girl's arms about her, and, bending to the bright head, kissed it twice. Phoebe, grown careless in her joy, ran down the walk to stop the approaching wagon; and when she looked round, Dorcas had shut the door and gone in. She waited a moment for her to reappear, and then, remembering the doctor had had no breakfast, she stepped into the wagon, and they drove happily away. Dorcas went to her bedroom, touching the walls, on the way, with her groping hands.

She sat down on the floor there, and rested her head against a chair. Once only did she rouse herself, and that was to go into the kitchen and set away the great bowl of _blank-mange_ she had been making for dinner. She had not strained it all, and the sea-weed was drying on the sieve. Then she went back into the bedroom, and pulled down the green slat curtains with a shaking hand. Twice her father called her to bring his sermons, but she only answered, "Yes, father!" in dull acquiescence, and did not move. She was benumbed, sunken in a gulf of shame, too faint and cold to save her by struggling. Her poor innocent little fictions made themselves into lurid writings on her brain. She had called him hers while another woman held his vows, and she was degraded. Her soul was wrecked as truly as if the whole world knew it, and could cry to her "Shame!" and "Shame!"

The church-bells clanged out their judgment of her. A new thought awakened her to a new despair. She was not fit to teach in Sunday-school any more. Her girls, her innocent, sweet girls! There was contagion in her very breath. They must be saved from it; else when they were old women like her, some sudden vice of tainted blood might rise up in them, no one would know why, and breed disease and shame. She started to her feet. Her knees trembling under her, she ran out of the house, and hid herself behind the great lilac-bush by the gate. Deacon Caleb Rivers came jogging past, late for church, but driving none the less moderately.

His placid-faced wife sat beside him; and Dorcas, stepping out to stop them, wondered, with a wild pang of perplexity over the things of this world, if 'Mandy Rivers had ever known the feeling of death in the soul. Caleb pulled up. "I can't come to Sunday-school, to-day," called Dorcas, stridently. "You tell them to give Phoebe my class. And ask her if she'll keep it. I sha'n't teach any more." "Ain't your father so well?" asked Mrs. Rivers, sympathetically, bending forward and smoothing her mitts. Dorcas caught at the reason. "I sha'n't leave him anymore," she said. "You tell 'em so. You fix it." Caleb drove on, and she went back into the house, shrinking under the brightness of the air which seemed to quiver so before her eyes. She went into her father's room, where he was awake and wondering.

"Seems to me I heard the bells," he said, in his gentle fashion. "Or have we had the 'hymns, an' got to the sermon?" Dorcas fell on her knees by the bedside. "Father," she began, with difficulty, her cheek laid on the bedclothes beside his hand, "there was a sermon about women that are lost. What was that?" "Why, yes," answered the parson, rousing to an active joy in his work. "'Neither do I condemn thee!' That was it. You git it, Dorcas! We must remember such poor creatur's; though, Lord be praised! there ain't many round here. We must remember an' pray for 'em." But Dorcas did not rise. "Is there any hope for them, father?" she asked, her voice muffled. "Can they be saved?" "Why, don't you remember the poor creatur' that come here an' asked that very question because she heard I said the Lord was pitiful? Her baby was born out in the medder, an' died the next day; an' she got up out of her sickbed at the Poorhouse, an' come totterin' up here, to ask if there was any use in her sayin', 'Lord, be merciful to me, a sinner!' An' your mother took her in, an' laid her down on this very bed, an' she died here.

The dusk sifted in about the house, faster and faster; a whippoorwill cried from the woods. So she sat until the twilight had vanished, and another of the invisible genii was at hand, saying, "I am Night." "Dorcas!" called the parson again. He had been asleep, and seemed now to be holding himself back from a broken dream. "Dorcas, has your mother come in yet?" "No, father." "Well, you wake me up when you see her down the road; and then you go an' carry her a shawl. I dunno what to make o' that cough!" His voice trailed sleepily off, and Dorcas rose and tiptoed out of the room. She felt the blood in her face; her ears thrilled noisily.

An' your mother hil' her in her arms when she died. You ask her if she didn't!" The effort of continuous talking wearied him, and presently he dozed off. Once he woke, and Dorcas was still on her knees, her head abased. "Dorcas!" he said, and she answered, "Yes, father!" without raising it; and he slept again. The bell struck, for the end of service. The parson was awake. He stretched out his hand, and it trembled a moment and then fell on his daughter's lowly head. "The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ--" the parson said, and went clearly on to the solemn close. "Father," said Dorcas. "Father!" She seemed to be crying to one afar. "Say the other verse, too. What He told the woman." His hand still on her head, the parson repeated, with a wistful tenderness stretching back over the past. "'Neither do I condemn thee; go, and sin no more.'"

COMMENTS