What’s to watch on Netflix?

- 20 Apr - 26 Apr, 2024

Darren Aronofsky appears to be a director who is obsessed with extremes. With Black Swan, he demonstrated how far one can go to achieve perfection. It was the depths to which an addict can spiral in Requiem For A Dream. Extremism is expressed in The Whale by a man named Charlie (Brendan Fraser), who pushes human limits with his size and hermetic lifestyle. What's interesting is that the most resonant parts of this film – and Charlie – are found in the ordinary, not the extraordinary.

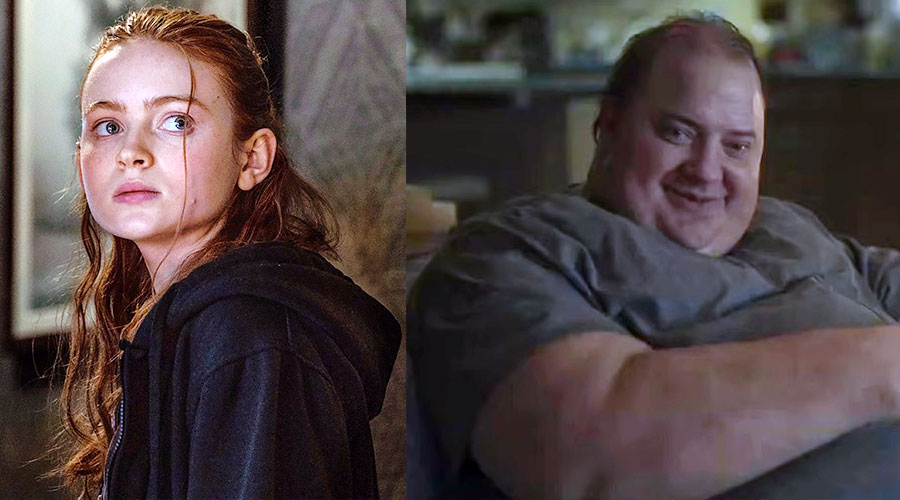

Charlie's physical form – delivered via relatively convincing (though still inherently dehumanising) prosthetics – is the headline, the audience draw, the thing to be ogled at. He is extremely obese. His stomach hangs over his pants. His jawline blends into his neck. Aronofsky's direction – and Samuel D. Hunter's script, adapted from his own play – shows a lot of compassion for Charlie, but can't resist the urge to exploit his size. His fatness is something to be judged, pitied, and explained away, and while the supporting characters mostly avoid doing so, the film itself does little to interrogate the real-world stigma that someone like Charlie faces, and how it would exacerbate his trauma, shame, and guilt.

Charlie's behaviour is more compelling than his body – his routine of ordering a pizza and hiding from the delivery man; pretending his webcam is broken so his students don't see him; and self-destructive snacking habits that have little to do with food and everything to do with his feelings. What little new ground The Whale finds in its portrayal of fatness, it makes up for in its honesty about the relentless, oppressive experience of disordered eating.

All of that aside, it's The Whale's theatrical origins and how they translate to a film adaptation that weigh the most on it. The single location effectively conveys Charlie's isolation, but the cold palette and lack of visual variety become stale after a while. Time spent fleshing out the backstory of do-gooder missionary Thomas (Ty Simpkins) feels squandered, and it is by far the least engaging thread.

Brendan Fraser is unquestionably the hero. It's impossible not to see thematic parallels between his experiences in (and withdrawal from) Hollywood and Charlie's isolation from the world. His screen presence adds much-needed empathy to this film, bringing lightness and innocence to a character who is both selfless and selfish; incredibly optimistic about his daughter Ellie's (a spiky, excellent Sadie Sink) potential but hopeless about his own; able to see his flaws but refuse to accept responsibility for them. As difficult as this may have been for Fraser, seeing him given the space to play such a complex role in such a thoughtful, humane manner is The Whale's true triumph.

COMMENTS