MUSLIMS ENTER AMERICAN POLITICS

- 10 Nov - 16 Nov, 2018

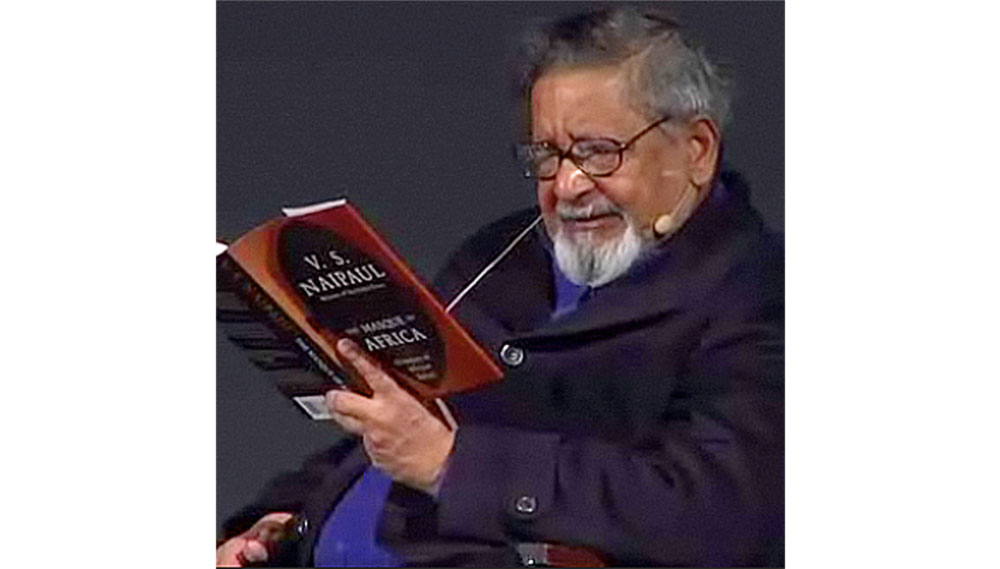

V.S. Naipaul was important to me at a crucial early point in my adult life and career. Many other things can be said about him – and those other things have all been said, ad nauseum, for decades. I’ve said many of them myself. And many of the same old things – pro, con, and nuanced – have been said all over again since the great writer’s death August 11, just six days before his 86th birthday. In this space this week, what I want to say is something that only I can say, about how I’m lastingly grateful to him for the crucial role he had played in opening the wider world to one particular young provincial American.

Naipaul was ideologically controversial as well as, by all accounts, not personally likeable. And his younger “frenemy” (the term is silly and anachronistic, but apt) Paul Theroux was in some ways more important to me as a role model, for showing that it was possible for a writer to be at once thoroughly cosmopolitan and unapologetically American. And Theroux could be incisive where Naipaul was evasive. Thus, in some ways, Theroux’s memoir Sir Vidia’s Shadow is as crucial a document to understanding and appreciating Naipaul as any of Naipaul’s own books. (I was pleased to be able to express my own sense of this to Theroux himself, when he came to Seattle on a book tour a decade ago. I purchased a paperback copy of Sir Vidia’s Shadow, along with his then-new book Ghost Train to the Eastern Star, and stood in line to have them signed. Theroux tapped Sir Vidia’s Shadow and asked me, “Have you read this one?” “Yeah, it’s a masterpiece,” I replied. He then offered me his hand to shake and said, fulsomely, “Thank you!”)

But my discovery of Naipaul himself was really where it all began for me as a would-be world-traveling writer. I began reading him after stumbling on a copy of An Area of Darkness in a used bookshop in Kathmandu in 1986. I was moved to binge-read most of the rest of his oeuvre over the next decade by the quality of his writing as well as by the discoveries, both literal and literary, that it made available to me. There are allusions to Naipaul’s influence sprinkled through my book Alive and Well in Pakistan. I quote the inscription Theroux wrote in the journalist Ahmed Rashid’s copy of Sir Vidia’s Shadow (“with gratitude for your wise counsel”), and the artist Salima Hashmi’s comment about having met Naipaul (“I thought A House for Mr. Biswas was his best book. But I also thought that if I passed such a comment, I would stall the dinner party.”) But, above all, in the early chapters of Alive and Well in Pakistan I recount my travels very literally in Naipaul’s footsteps in Indian-held Kashmir, which in turn led very directly to my discovery of and lifelong fondness for Pakistan. (I had an opportunity to express a thought-through and appropriate measure of fealty to this aspect of Naipaul’s influence in November 2015, when I was invited to give a talk about Pakistan at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.)

“All those places will be Haiti in the end,” Naipaul once told interviewer Scott Winokur of the San Francisco Examiner, specifically referring to Caribbean islands like Trinidad, where he grew up. He was right enough about that. But what neither Naipaul nor his liberal (and not-so-liberal) Western admirers and apologists were willing to do was to take the next step: admitting that all places blighted by human civilization will be Haiti in the end, so to speak. Haiti – a country I know well at first hand – has always been ahead of the curve, always prophetically ahead of the rest of us, to its great misfortune. And, by this late date, surely no honest American or European can any longer feel smug about where our “developed” societies are at, or where they’re heading.

And this is where the ideological fault lines that Naipaul’s work defines matter. Honesty of depiction, based on direct witness and experience, is an important literary value, the bread and butter of any true writer’s craft. And much – perhaps most – of Naipaul’s writing exhibits this quality. I would single out An Area of Darkness – his 1964 account of his first journey to India and Kashmir at age 29, and perhaps my favorite of his books – as well as his meditative late masterpiece The Enigma of Arrival, as works in which Naipaul rose fully to the occasion. But it’s possible for a writer to depict honestly, yet to interpret either dishonestly or incompetently. And, later in his career, as Naipaul began getting too much of the wrong kind of praise, he came to take entirely too much pleasure in the sound of his own provocative and presumptively authoritative voice. This regrettable turn began around the time of his ambitious travel book Among the Believers (1981), which covered four Muslim-majority countries including Pakistan and Iran, and whose publication – whether fortuitous or calculated – came just after the Iranian revolution.

It was Among the Believers that landed Naipaul on the cover of Newsweek magazine and made him famous in the USA. It wasn’t all downhill from there – The Enigma of Arrival was published in 1987 – but his American travel book A Turn in the South (1989) was slight and forgettable, and India: A Million Mutinies Now (1990) was simultaneously a baggy mess and an embarrassing paean to ascendant Hindu nationalism. I was still in my Naipaul-worshiping phase when I read it, and even I cringed at the cynicism of its fawning toward the Indian right wing.

We could argue these points endlessly – but we already have, haven’t we? All I want to say about V.S. Naipaul at this point, now that he’s gone, is that I remain personally deeply grateful to him, for having blazed a trail that allowed me to see the entire wide world as my own legitimate subject matter. •

COMMENTS